© FURTHER, All Rights Reserved. 31 Jan 2022. No alteration or reproduction without express permission.

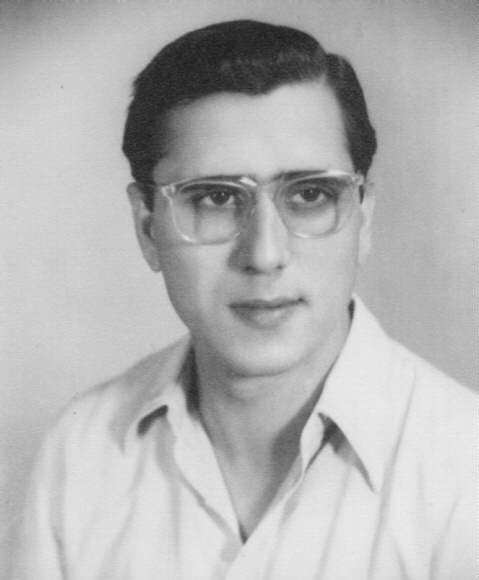

PA-2709, Brig. Fazal Ur Raheem, was born Mian Fazal-e-Raheem on 1 April 1926 in Dheri Khel, a rural suburb across the Kabul River from Nowshera. Among all his course-mates and students at the Pakistan Military Academy, he was popularly and fondly known as Mian Sahib.

Childhood

He was the first-born of Mian Fazal Karim and Wazir Begum. She died of tuberculosis in 1930, having given birth to another son, the late Col. Rehmatullah. Mian Karim, a Captain in the British Indian Army, was often posted to places he couldn’t take his boys along – the longest being a 4-year WWII stint in Egypt during which he was injured in a road accident while on duty. So even though the Captain’s elders got him re-married soon after his wife’s death, the boys spent their early years in various houses under the watch of aunts and grannies.

In Dheri Khel: A lad who lost his mother

The new Karim household was a busy one. Over the next 20 years, an estimated 10 children were born of which 6 survived. Naturally, Mian Sahib’s early years were difficult. He felt lonely and neglected. His father loved him, but duty kept the Captain away for long periods. The boy’s love for his father, and how it was reciprocated, was to become the supreme motivational force in his life. He loved and served humanity in general, but in particular he loved and served tirelessly, through old age and terminal illness, the children and grand-children of a father whose love and kindness he could not repay.

Given his sensibilities and noetic bend, he took to books at an early age to mitigate his loneliness. His teenage favourite was Wilde’s De Profundis. That a work so sombre and so hauntingly beautiful would appeal to someone so young spoke of his intellect and aesthetics, developed well beyond his years. Rupert Brooke too was a youthful favourite. He was growing into an articulate, soft-spoken, handsome young man with an uncanny command of English, Urdu, Punjabi and Pushto. He spoke all four with such ease and grace, without hint of a regional accent, that most of his mates couldn’t tell his ethnic origin. At his funeral in 2010, a childhood friend, Dr. Idris, memorably said: “He was the most beautiful man to be ever born in Nowshera. Every time he spoke, it was as if flowers not words were emanating from his mouth.” As he matured, Mian Sahib loved Ghalib, Iqbal and later Faiz for their subtle treatment of themes such as liberty, duty, individuality and loneliness. He took heart from knowing that others far more talented than him, far more accomplished, had suffered far more. He began to understand the nature of suffering and the central importance of humility to human fragility.

This fascination with suffering and humility was to become a source of self-evaluation throughout Mian Sahib’s life. He would always measure himself by his ability to deal with adversity and to be humble in success. In his diaries, he is often livid with himself for not being humble enough. He would be hard on himself, with vicious self-analysis – a quality that turned him into a hard-task-master who often brought out the best in himself and his charges. But, having lost his mother at four, he was equally cognisant of people’s emotional needs. The deprivation at the heart of his own suffering had turned him into an empath; he was highly sensitive to others’ plight.

Youth and College

Upon matriculation in 1942, Mian Sahib gained admission to Islamia College Peshawar. To drop him off at the hostel, his father rode the bus with him from Nowshera. He bought his son a new pair of shoes, a hockey stick and some books. The boy loved hockey and sports in general, much as he loved books. As they bid farewell by the lush-green lawns of the College in front of the imposing edifice, Mian Karim had tears in his eyes. He wondered if the world would acknowledge the gem he was leaving at its doorstep. He spoke a few words of affection, but none of concern. He wasn’t concerned because he knew what the boy was made of – he didn’t need to tell his son how to behave or what to do. Nevertheless, feelings had the better of him. Even at such a tender moment, the boy remained composed and comforted his father.

His shoes were stolen within the first week. He would wear them everywhere but not when playing hockey. He would polish them vigorously and look proudly at them often. He would put them by the side of the field, shining and conspicuous, while he played barefoot. Sure enough, one September evening they were stolen from the sideline. The boy wrote to his father, apologising and reassuring him that the old pair would do splendidly. The father wrote back, only to reaffirm his love. Even on his death-bed, nearly 70 years later, the son would raise a trembling finger at his father’s portrait on the wall to recall the man’s generous, forgiving nature and feel touched. It was a love for the ages.

In that part of India, Islamia College was an illustrious institution of its time. Here at last, for the first time in his life, Mian Sahib found himself among kindred spirits. He developed a certain pride in his alma mater and years later described it thus:

“The college had an excellent faculty. The Principal, Dr. Umar Hayat Malik, had a PhD in Mathematics from the UK. The Head of the English Department was Mr. Harris, a Scotsman devoted to English literature. When Dr. Malik was selected as Director Statistics and posted to New Delhi, Mr. I.D. Scott, who was M.A. Oxford and belonged to ICS cadre, replaced him as the Principal. Professor Mohammad Farid was the Head of the Department of History. He was an honours graduate in History from a British university. The Dean of Islamic Studies was a graduate of Al-Azhar University.”

Pakistan Movement

Mian Sahib was an early, wholehearted, and permanent convert to the idea of Pakistan. Even when in old age he lamented the sorry state of affairs in the country, he maintained that Jinnah had done the right thing by fighting for the nation-state and winning its independence. This loyalty to Jinnah and Pakistan came about through a series of experiences at Islamia College. In 1944, he was elected Secretary of the Khyber Union, the student union at the College. It was a prestigious office and it marked the coming of age of his political consciousness. It was also an early introduction to democratic values that he lived by all his life, in spite of being a soldier. He knew India was not going to be a free country if its young people kept lingering on the fence. He educated himself to be able to evaluate the politics and society of India so that he could understand his identity and choose a side.

He had lived in a Muslim majority region all his life, but his father’s various postings had given him plenty of exposure to other communities. From this experience, he gleaned that India was made up of several cultures based on language, food, customs, superstition, ritual and belief. While the rest of India’s cultures had been dominated and assimilated for millennia by Hindu ritual and tradition, Islamic culture had stood apart. The divisiveness of Brahmanism – labelling human beings from beneath touchable to above reproach based only on descent – was abhorrent to many. Yet, in spite of suffering this self-serving Brahmin culture for millennia, other castes and minorities in India had learned to accept and live with it. But not Muslims. They believed their culture was more egalitarian and therefore more modern and pragmatic.

From his study of history, Mian Sahib concluded that Hindus had been particularly servile to the British and had in fact helped the latter defeat the Mughals in the hope of regaining their lost empire. While he did not hold this against the Hindus, for it was a natural act of self-interest, he felt that history had thus pitted Hindus and Muslims in opposing positions with differing interests. In his view, by cooperating with the British for 200 years, Hindus had begun to monopolise both high office and big business in India and they fully intended to consolidate this monopoly after independence. Since Muslims viewed the Hindu domination of government and business during the British rule as an act of treachery and betrayal, the heat of friction after independence could ignite a fire. He didn’t know that India was bound to burn anyway.

So he chose his side and became fervently active in the student movement for Pakistan. In that capacity, he met Jinnah when the leader came to address the youth in Peshawar in 1945. The young man was deeply impressed, as much by the gentleman’s clarity of vision and command of language as by his attire and “Englishness.” Here was somebody who could pass for an Englishman and yet was fighting to end British rule in India. This, to Mian Sahib, was the epitome of the civilised man: Someone whose guise belied a fierce independence, who could be himself without calling any attention to himself. No half-naked gimmicks of the Congress leaders, no use of young women as crutches, just a straight-talking, straight-walking, English-looking gentleman who had become the bane of the English. The sheer romance and irony of this was an epiphany for the literary young man.

Ambition and Sacrifice

Mian Sahib graduated from Islamia College with a B.A. in Political Science in 1946. His friends now included the younger of his professors as well as the sons of many prominent families in the region. He was reading voraciously and writing copiously. During these years, he wanted variously to become a doctor, a writer, an actor, and sometimes even a critic. He acted out entire scenes of movies and plays after watching a performance with his friends. One of them, Yoosof Sawal, later an editor at the Financial Times, recalled with immense fondness: “His memory was phenomenal. He would remember significant dialogues, word for word, and repeat them to our delight. He would even write his own little skits and perform them for us.”

But all of that was little more than flirting with fate. Deep down, he knew that none of it was to be. His beloved father had 10 mouths to feed and no plans for feeding them. Settling back in his ancestral home in Dheri Khel after retirement, Mian Karim had occupied himself with public welfare. Among other things, he commissioned a committee for constructing the Nowshera College and worked tirelessly until the co-educational institution was completed a decade later. Meanwhile, the house was run on his paltry pension. Ten mouths could not be fed on that, let alone clothed or educated, and Mian Sahib was now ready to mortgage his life to pay his father’s outstanding debts and obligations to his progeny. His family in Dheri Khel had no idea that out of his love for his father he would soon fill a role so far beyond his years that even his love of literature and history would seem trivial in comparison. That he was about to set sail, for their sake, on a course in whose wake all his personal desire and ambition would be swept away forever.

PMA, Fort Benning, and Queenscliff

Once the dream of Pakistan was realised, Mian Sahib’s sole purpose in life was to ease his father’s financial burden of raising many children. But making a living would not be enough – he needed something that would also channel his youthful, emotional and patriotic energies. So he applied for the 1st PMA Long Course and, small wonder given his academic and athletic ability, got in. In his own words, “Days passed into weeks and months into years, with a new challenge every day, until I found myself marching up the steps and standing in front of Quaid-e-Millat Liaquat Ali Khan on 4 Feb 1950.”

He graduated as a second-lieutenant near the top of his class, being an Under Officer of Khalid Company, and was commissioned into 19 Punjab Regiment in Sylhet, East Pakistan. The CO appointed him Unit Intelligence Officer. “I thus learnt in 19 Punjab the nuts and bolts of minor tactics through company and platoon level exercises with troops. After four years with the Battalion, I was selected to be an instructor at the PMA. My experiences with 19 Punjab and my earlier training at the PMA provided me a solid base for my job as Platoon Commander of 14 PMA Long Course.” In the next few years, he was selected for two prestigious overseas courses: A year-long professional course in 1957 at the venerated US School of Infantry in Fort Benning, Georgia, and then in 1959 another year at the renowned Australian Staff College in Queenscliff, Victoria.

‘65 War and 17 Punjab Haideri

Upon his return in 1960, he was posted to the General Staff Branch at GHQ and then to 17 Punjab in 1963. “I felt a personal attachment with this regiment because my course mate, Raja Aziz Bhatti, had been posted to 17 Punjab after receiving the Sword of Honour.” By now, Mian Sahib was well-reputed for his robust intellect and incisive analysis. With tensions escalating on the border in December 1964, his exceptional analytical skills were needed at the ISI Directorate. He served there in a crucial role throughout the war and filmed a documentary on espionage tactics which is still shown to students at the Intelligence School.

After the war, he was promoted to Lt. Col. and posted as Commanding Officer of the one-and-only 17th Battalion of the Punjab Regiment in Jessore, East Pakistan. Only a few months earlier, Maj. Bhatti had forever enhanced the prestige of this battalion through exceptional gallantry that cost him his life and earned him the only Nishan-e-Haider of that war. The battalion had been renamed 17 Punjab Haideri in recognition of Bhatti’s ultimate sacrifice and Mian Sahib felt deeply honoured to lead it so soon after his friend’s heroics. His ACR dated 19 September 1966, confirming him as CO 17 Punjab, says:

“A capable and conscientious officer who possesses sound knowledge of his own as well as other arms of service. He is very quick on the up-take and his performance on exercises and tasks assigned to him has been of a high order. He is entirely dependable, has plenty of drive and shows good judgment in delegating responsibility to his subordinates. He is co-operative and willing worker with a steady, even and equable temperament. He is frank, tactful and has pleasant manners for which he is well-liked by his superiors, equals and juniors…. He is impartial, free from bias and a good disciplinarian. He has good sense of humour and socially mixes well and correctly.”

‘71 War and Final Assignments

In 1969, he was appointed GSO-I at the Command and Staff College, Quetta, where he wrote a clairvoyant paper building an historical and philosophical case for national defence. He wrote several other papers on tactical and strategic issues, including the challenges of dealing with Afghanistan. Ever a man of peace, he argued for the imperative of friendly relations with all neighbours and for a national army to secure not only the borders of the Republic but also the rights of its citizens. His ideas were brilliant but radical and may not have found a voice had it not been for the kindred spirit of the Commandant. Maj. Gen. Mohammad Sharif (later Chairman JCSC) wholeheartedly believed in his G-I’s depth of analysis and impeccable logic and encouraged his vision. Each his own man, yet the two formed a lifelong bond to which words like friend and colleague cannot do justice.

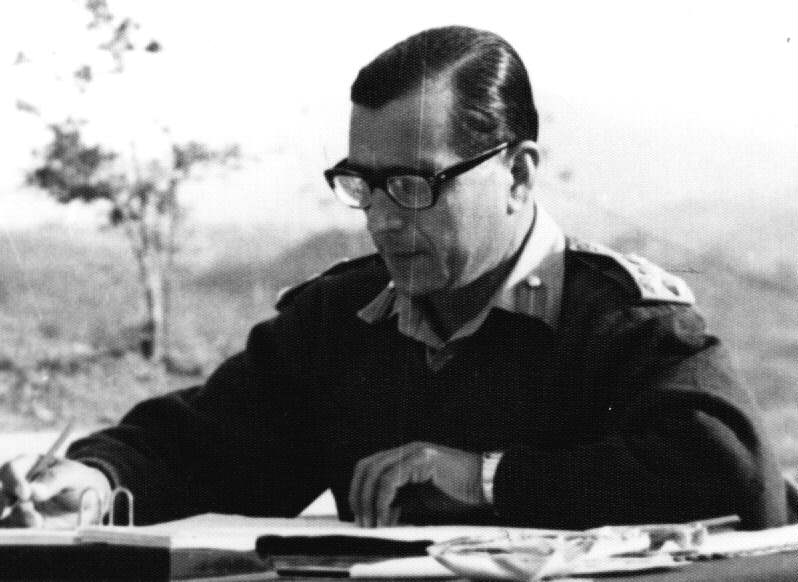

Shortly thereafter, Mian Sahib was promoted and posted as Colonel Staff of an infantry division at Sialkot. He became a Brigadier in 1970 and was placed in command of 7 AK Brigade at Jari Kas.

H e had already served in the area as a Major and was well-acquainted with the terrain. Recalling his experiences as Colonel Staff in Sialkot, he engaged the services of the Engineer Company Commander to renovate the bunkers and other repairable defenses. This turned out to be both a prescient and a decisive preparation. The GOC 23 Division recognised that and wrote to him on 20 September 1971, weeks before war broke out: “I must thank you for your dedication resulting in improvements in the standard of training, discipline and preparedness for war… I am confident 23 Division will give an excellent account of itself if and when called upon to do its duty in any future conflict.”

Holding the Division’s left flank during the ‘71 conflict, his brigade took an aggressive-defense posture to frustrate the opposition’s attempts at infiltrating from the flank. The 7 AK’s defenses were so impenetrable that some of its battalions were even able to make inroads. Mian Sahib thus became one of the few commanders who advanced on Indian-held territory during that conflict. After the war, the captured territory was used as a bargaining chip to revert the cease-fire line back to the 1948 positions. GOC 23 Div wrote to him on 13 January 1973:

“I take this opportunity to express my gratitude to you and through you to all ranks of 7 AK Brigade…. You have commanded this Brigade resolutely, firmly and justly which I greatly appreciate and which has gone a long way in making our mission a success.”

In the Spring of 1973, Mian Sahib was a passenger in a road accident while returning from an inspection tour in his Brigade area on his Jeep. He was hospitalized for two months and eventually lost his medical category. His last command was 77 Brigade in Kharian (first under 19 Div and later under 17 Div). On 15 August 1973, GOC 19 Division wrote to him:

“I have been deeply touched by the spirit of patriotism and dedication with which you addressed yourself to the problems of dev of defense-works and comms in your area in particular to the gen improvement of cbt efficiency of your fmn. I hope one day these efforts will bear fruit and we all will fondly recall your contribution towards this war effort. You also have the privilege of having fought a war with your bde and in which you had given a good acct of yourselves. This is something of which anyone can justly feel proud.”

Post-Army

In 1973, several vacancies were announced in the Civil Service of Pakistan because of the departure of scores of Bengali officers who had chosen to migrate to Bangladesh. Mian Sahib enrolled for the Lateral Entry Examination along with 35,000 other candidates from all across Pakistan and stood 5th in the published merit list. He took voluntary retirement from the Army and joined the Civil Service in 1975. GOC 17 Div had this to say to him on 1 March 1975: “Having seen the MS letter regarding your most richly deserved appointment as Joint Secretary in the Planning Division of the Federal Government, it is almost certain that you shall be painfully departing from us. On the one hand I am indeed very happy that you have been selected for this high post in the Central Government which you deserve every bit, however, on the other hand, I earnestly believe that the departure of a very bright career officer like yourself from the Army shall be a great loss…. I am indeed grateful to you to have so devotedly and efficiently led your Brigade under my command. Your contributions towards training and operational preparedness of 17 Division have been enormously befitting and rich in dividends…. I value a great deal my friendship and brotherhood with a magnificent personality like yourself.”

In 1981, he was in a UN Fellowship Program at the US Office of Personnel Management. The Program Director’s words reflect something of Mian Sahib’s “magnificent” personality: “Mr. Raheem is a highly sophisticated and polished gentleman who reflects honor and dignity on his Government service. He was keenly interested in the US system of public administration and everyone with whom he met was impressed with him. It would indeed be a pleasure to welcome other Pakistani officials of his high caliber.”

As Managing Director of the Benevolent and Group Insurance Funds from 1982 to 1986, he brought that institution from the brink of bankruptcy to a state of enviable health. The Establishment Secretary had this to say in his Summary for the Prime Minister: “As a result of dedicated efforts of Brig. Fazal-ur-Raheem the total assets of the Fund have increased from Rs. 60.37 million in 1982/83 to Rs. 101.56 million in 1984-85 with an average profit of over Rs. 2 million per month during the 1984/85 financial year. Benevolent Fund Building was completed in record time and long outstanding cases were settled without recourse to litigation. The total number of outstanding cases that amounted to 727 in 1981/82 were reduced to 197 in 1984/85.… The Board of Trustees was able to show a total savings of Rs. 12 million in 1984/85 as compared to an approximate total of 0.6 million in 1982/83.”

Retirement and the Inevitable

Mian Sahib retired as Additional Secretary (Establishment) in 1986 upon turning 60 and did not seek any extensions. He had a legion of close friends in both the military and the civil service – like the late Gen. Sharif, the late Brig. Luqman Mehmood, and others. His greatest joy in retirement was to shoot the breeze for hours with such friends in person or on the phone. As in service so in retirement, he accosted people only for their company and not for what they could do for him. He continued to work for the welfare of his father’s children and grandchildren. This is how he occupied the last 24 years of his life, quietly, and passed away peacefully at 11:09 AM on the 28th of September 2010, surrounded by those who loved him.

All through his service to the nation, Mian Sahib claimed no credit nor ever kept a paisa for himself. He insisted on serving humanity but never a man, not even himself. His humble house and modest means are forever a testament to the gem his father had placed at the world’s doorstep in 1942. That new pair of shoes wasn’t the only thing he was happy to live without. He lived on little and shared all he had. His generosity did not end with his life: the Fazal Ur Raheem Trust for Healthcare, Education and Relief (FURTHER) has helped graduate 44 students with professional degrees in Medicine, Dentistry, Engineering, and IT. Paraphrased, some of his favourite lines from The Soldier serve him well:

If I should die, think only this of me:

That there’s some corner of a fertile field

That is forever peaceful. There shall be

In that rich earth a richer dust concealed;